Regular readers of this blog will be familiar with my series on rhetorical devices. Figures of rhetoric such as anaphora, epistrophe, epizeuxis and others, when used properly, can set a speech on fire so that it blazes in the memories of those who heard it long after the speaker has left the stage.

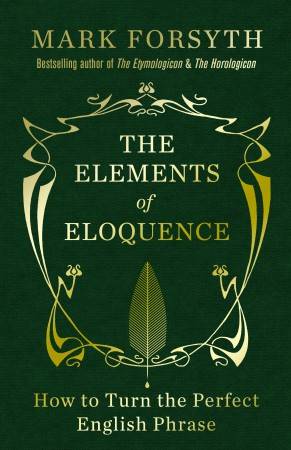

Thus, I was delighted when the good people at Icon Books sent me a complimentary copy of Mark Forsyth’s The Elements of Eloquence.

In his book, Forsyth takes us through 39 chapters, each one devoted to a specific rhetorical device. Forsyth has a writing style that make you feel as though you are chatting with a friend over a beer. (And when good friends get together for a beer, what else do they talk about besides rhetoric?) He also has a wry, and often wicked, sense of humour. Take, for example, this commentary on alliteration:

You can spend all day trying to think of some universal truth to set down on paper, and some poets try that. Shakespeare knew that it’s much easier to string together some words beginning with the same letter. It doesn’t matter what it’s about. It can be the exact depth in the sea to which a chap’s corpse has been sunk; hardly a matter of universal interest, but if you say, “Full fathom five your father lies”, you will be considered the greatest poet that ever lived. Express precisely the same thought in any other way – e.g. “your father’s corpse is 9.144 metres below sea level” – and you’re just a coastguard with some bad news.

Or this remark on syllepsis (when one word–often a verb–is used in two different ways, or applied to two different things):

But the commonest form [of syllepsis] is the simple contrast of the concrete and the abstract. When the prophet Joel told the people of Israel to “Rend your heart and not your garments” he was using the same trick that the prophet Mick Jagger employed when he talked in one song [Honky Tonk Woman] about a lady who was not only able to blow his nose, but his mind, although for rather different purposes. Indeed, one suspects that Mr Jagger was planning another syllepsis based on blow that would have got the song banned on radio.

Forsyth frequently draws on examples from the usual suspects such as the Bible, Shakespeare and Churchill. But he also welcomes rhetorical devices from singers, such the Beatles, Supertramp, Leonard Cohen, INXS and Alanis Morissette, and movies such as Dirty Harry, Pulp Fiction, Austin Powers and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels.

This book is an excellent reference guide on rhetoric. However, with a writing style that borders on the conversational, and with chapters averaging only four to five pages in length, The Elements of Eloquence is a light read. Indeed, Forsyth ends each chapter with an example of a new rhetorical device that leads to the next chapter.

I recommend The Elements of Eloquence to anyone looking to spice up their speeches or writing. Will I refer refer to Forsyth’s book in future posts on rhetorical devices? Indeed I will; of that you can be certain; indeed I will. (And that’s hypophora and diacope.)

4 Replies to “The Elements of Eloquence”

It’s been on my shelf for a number of years John. Thanks for reminding me to get it down.

I enjoyed this very much and am glad of the book (you can feel the ‘however’ coming, can’t you?) but I am, I confess. reminded of Bertrand Russell. ‘To acquire immunity to eloquence is of the utmost importance to the citizens of a democracy.’ Though his quote is in itself eloquent, it reminds me not to become so enamored of the beauty of words that I forget content. That said, I’ll probably get a copy. Thanks.

Cheers, Olivia. You will enjoy it.

Thanks, Bob. Indeed, eloquence, when taken to its extremes, can beguile us to the point that where we fail to realise that there is no point! Worse still is when eloquence leads us down a road which, with hindsight, we will bitterly regret. Still, a speech that wraps great content in great language is the best kind of speech.