Giving a speech or presentation can be stressful. Public speaking anxiety is a problem for many people. Even seasoned public speakers get butterflies in their stomachs prior to stepping on stage.

Most people deal with the pressure by trying to calm down. They sit quietly and tell themselves, silently or aloud, to calm down, that there is nothing to worry about, etc. But recent research suggests that this might be the wrong strategy.

Trying to calm down is a bad strategy

In a paper in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, which is published by the American Psychological Association, Professor Alison Wood Brooks of the Harvard Business School found that “[a]n overwhelming majority of people (more than 90%) believe the best way to manage pre-performance anxiety is to ‘try to calm down'”. Brooks believes that a better approach is to reframe the anxiety as excitement.

Drawing on previous research, Professor Brooks describes anxiety as “a state of distress and/or physiological arousal in reaction to stimuli including novel situations and the potential for undesirable outcomes”. Such stimuli include singing in front of others, taking a test, having a job interview and speaking in public.

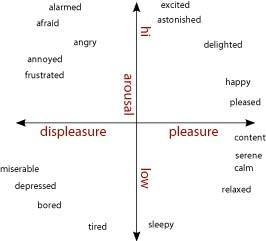

All psychological states share two attributes: arousal and valence. Arousal can be high (e.g., afraid, excited) or low (e.g., bored, relaxed). Valence refers to whether a psychological state is positive (e.g., excited, relaxed) or negative (e.g., afraid bored.) Thus, there are four quadrants to psychological states as in the grid below.

Research shows that trying to decrease anxiety before an event is difficult (because high arousal is automatic) and often ineffective. Professor Brooks writes that when you try to calm down before an anxiety-producing event, you are trying to shift both your arousal (from high to low) and your valence (from negative to positive).

Time to get excited

It is much better, in her opinion, to reframe the anxiety as excitement because anxiety and excitement are both high arousal psychological states. Professor Brooks says that they are arousal congruent. Thus, instead of trying to change both arousal and valence, with Professor Brook’s approach, you only have to change valence.

So far, so good. But what do you have to do to get yourself in a positive frame of mind? According to Professor Brooks, it might be something very simple. She conducted several studies, the design and procedures of which are thoroughly detailed in her paper, which you can read here.

One of those tests involved public speaking. Participants had two minutes to prepare a speech on the topic, “Why you are a good work partner”. To increase the anxiety of the participants, Professor Brooks told them that they would deliver their speeches to an experimenter and that he would video the speeches for later judging by a “committee of peers”.

After preparing their speeches but before delivering them, participants were randomly assigned to say “I am excited” or “I am calm”. They then delivered their speeches. The experimenter and the independent raters who watched the videos did not know the experimental conditions and hypothesis.

Those participants who said “I am excited” spoke longer than those who said “I am calm”; they reported feeling more excited about their speeches; and they felt marginally more satisfied with their speeches. As for the (blind) evaluators, they found that the participants who had said “I am excited” were more persuasive, more competent and more confident than their counterparts.

Why excitement is good

On this particular test, Dr. Brooks concludes:

Being asked to give a 2-minute public speech on camera caused individuals to feel very anxious. Compared with reappraising their anxiety as calmness by stating “I am calm,” reappraising anxiety as excitement by stating “I am excited” caused individuals to feel more excited, to speak longer, and to be perceived as more persuasive, competent, confident, and persistent.

As to why reframing public speaking anxiety as excitement improves performance, Dr. Brooks posits:

[I]ndividuals in a positive affective state are more likely to interpret issues as opportunities, whereas individuals in a negative affective state are more likely to interpret issues as threats. In this way, excitement may prime an “opportunity” mind-set, whereas trying to calm down may perpetuate a “threat” mind-set.

…

[R]eappraising anxiety as excitement will cause individuals to adopt an opportunity mind-set and improve their performance, whereas reappraising anxiety as calmness will cause individuals to perpetuate the threat mind-set typically associated with feeling anxious.

Going forward

Dr. Brooks acknowledges the need for more research on this subject. She recognizes that other strategies, such as meditation, might be useful to calm down before anxiety-inducing events. And, of course, the timing of such strategies (e.g., one week before the event vs 15 minutes before the event) is important. But she maintains that her findings “demonstrate the profound control and influence we have over our own emotions.”

I found Dr. Brooks’ paper insightful for public speaking anxiety. When I began my speaking career, I would try to calm down before I stepped on stage. With time, I changed my approach, and began to “pump myself up” with positive messages about how I would perform. The latter approach boosts my confidence and helps me hit the stage with a high level of energy.

The way we verbalize and think about our feelings affects the way we actually feel. And how we feel has a big impact on how we perform. So the next time you have to speak in public, as you are getting ready to go on stage, instead of trying to calm down, get excited!

9 Replies to “Get excited before your next speech”

For many, anxiety and public speaking go together. When I teach adults or adolescents, I’m comfortable, but when I have to deliver a speech, I’m not. I’m nervous before stepping onto a stage. I’m nervous in front of a large audience. I’m nervous when it comes to public speaking.

Many people can relate to this kind of nervousness – the fear of public speaking that causes sweaty palms, a racing heart, fast and shallow breathing, shaky hands and legs and a general feeling of malaise. The scientific term for this fear is glossophobia, which means speech anxiety.

My husband, John Zimmer, is an expert in the field of public speaking and training. He has helped numerous people prepare for their speeches and overcome their fear. John recently published this post on an effective way to deal with public speaking anxiety. Here’s John.

Great post John. Happy Holidays to you and your family.

Thanks, Dave. The same to you and your family. All the best for a great 2015!

John

Thanks for sharing this, John. I’d heard of the tip about reframing nervousness as excitement, but didn’t realise there was research to back it up, too. Fascinating stuff.

The paper made for an interesting read. As the author says, more research is needed, and it would be interesting to break it down even further (cultures, speaking situations, etc.). Still, the paper provides a valuable insight that can help a lot of people.

Hi John,

thanks for this interesting post. Reading about re-stating the anxiety feeling as Calmness or as Excitement, you made me wonder if there is a third alternative.

In Lisbon, I once saw a bull fight by chance. The most awe-inspiring part were the Forcados, 8 unarmed men who caught the charging bull by its head, using only their arms. The first dived on the charging bull’s head, the others piled on top. The bull looked down at the floor somewhat surprised, as indeed you would with 8 men balancing on your head.

If I were to be the first man here, I would hope neither to pump myself nor to calm myself, but rather to seek poise, the balance that I need to move in any direction depending on the circumstances. In this state, I would hope to respond to the situation as is, not to what might be or what could be.

There is a similar message in the excellent parenting book, ‘Setting Limits for Your Strong Willed Child’ by Robert Mackenzie, (my kids got the companion volume ‘Coping with Strong Willed Parents’ for xmas LOL). The ‘family dance’ is described as the behaviour of a family that leads to conflict. E.g. The request ‘Can you clean your room’ is first ignored, so you shout, then you threaten, then you punish. The desired outcomes, compliance and family harmony are not achieved. Undesired outcomes are resentment, and nothing is learnt as the scene is repeated weekly.

Mackenzie’s suggestion is to decline the invitation to ‘dance’; to side-step emotions-provoking actions (various strategies are proposed); & to understand the drives of the child.

It is this latter, rational understanding, that is paralleled by the Forcados. They know that acting appropriately to the actual situation will lead to the desired outcome, whilst layering in undesirable actions (such as panicking, blinking, or running away), will lead to failure. In short, they succeed through poise, which is a state of being.

Coming back to your post, what if instead of seeking to change one’s reaction to the situation by saying ‘I am calm’ or ‘I am excited’, one stated only the facts, describing the situation as is, without layering on meaning? Enter Bruce Lee stage right.

Thanks for raising a great subject.

Yours in aspiration,

Ben

Hi Ben,

Thanks for taking the time to leave such a detailed comment. (It may well be the most comprehensive that I have ever received.) So, as a third approach, take a sort of Zen attitude: “This is the situation; now deal with it.”? Interesting idea. The concern that I would have would be that too much of a Zen attitude could result in a flat presentation. No enthusiasm for the subject. And that’s not a good idea. That doesn’t mean that a calm speech cannot be effective; it can. But there has to be some enthusiasm on the part of the speaker for the subject. Still, if it works … if it allows the speaker to be focused and clinical without losing enthusiasm for subject … why not? Have you tried this approach? If so, what was your experience?

Hi John,

first of all, this was a great article, very insightful to read!

Second, I totally agree with what you wrote on the Zen approach. I normally pump myself up before public speaking situations, but recently tried the calming approach, just before an impromptu speaking situation. I think the speach I gave was quite okay, but the first part did indeed lack enthusiasm. As I started very calm, I needed some time to get going and so maybe my opening wasn’t as powerful as it could have been.

On the other hand, in my experience, the potential pitfall of pumping yourself up is starting too early. I’ve had situations where I pumped myself up so much and so early, that by the time I actually started speaking, I was tired.

So I think one of the keys is figuring out when exactly should you start pumping your self up (and how). The Zen approach I think would be more useful during the preparations, or the days leading up to the performance. So for me, it’s a question of finding the right balance. And of course, I guess it’s different for different poeple.

What do you think?

Thank you again for this great article.

Best,

Peter

Thanks for the comment, Peter and for sharing the personal experience. You have focused on a key point: timing. My appraoch is exactly as you have stated towards the end of your comment. I try to be very Zen and focused during the preparation. On the day of the event, I start to get myself pumped up early, then relax and then get pumped up again just before going on stage.