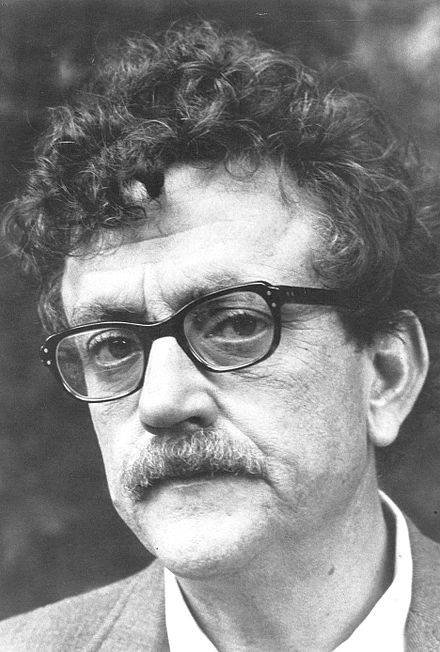

Kurt Vonnegut was one of the United States’ most intelligent, witty and beloved authors. His novels such as Slaughterhouse Five, Breakfast of Champions and The Sirens of Titan are still widely read and just as insightful as they were when they were first published.

In the 1980s, Vonnegut wrote a short essay entitled “How to Write with Style”. It appeared in the book How to Use the Power of the Printed Word. His advice is aimed at writers. However, as I reread the essay the other day, it struck me just how relevant Kurt Vonnegut’s advice is for speakers as well.

The essay is summarized below. The words in italics are from Kurt Vonnegut.

1. Examine your writing style

Why should you examine your writing style with the idea of improving it? Do so as a mark of respect for your readers, whatever you’re writing. If you scribble your thoughts any which way, your readers will surely feel that you care nothing about them. They will mark you down as an egomaniac or a chowderhead—or, worse, they will stop reading you.

Lesson: Improving the way in which your speeches and presentations are structured and delivered shows respect for your audience. You will also become a better speaker.

2. Find a subject you care about

Find a subject you care about and which you in your heart feel others should care about. It is this genuine caring, and not your games with language, which will be the most compelling and seductive element in your style.

Lesson: You should care about the subject of your talk. If you don’t, the audience will know. Audiences are smart; they can tell when a speaker is just going through the motions. All the flashy delivery techniques in the world will not save a talk if the speaker is not fully invested. So talk about something you care about. If you have to speak about a subject you don’t like, find a reason to care about it. If you can’t do that, find a reason why the audience should care. If you can’t do that, find someone else to do the presentation.

3. Do not ramble, though

I won’t ramble on about that.

Lesson: Keep things tight and focused. Everything in your talk—stories, data, slides, anecdotes, exercises—should support the message and further the objective.

4. Keep it simple

Remember that two great masters of language, William Shakespeare and James Joyce, wrote sentences which were almost childlike when their subjects were most profound. “To be or not to be?” asks Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The longest word is three letters long. Joyce, when he was frisky, could put together a sentence as intricate and as glittering as a necklace for Cleopatra, but my favorite sentence in his short story “Eveline” is this one: “She was tired.” At that point in the story, no other words could break the heart of a reader as those three words do.

Simplicity of language is not only reputable, but perhaps even sacred.

Lesson: Too many people are afraid to use simple words. They worry that the audience will think them unsophisticated or just plain stupid. Nonsense. Winston Churchill said that, broadly speaking, the short words are the best and the old words best of all. By some estimates, more than 70% of the words in English are monosyllabic. Use them!

Likewise, look for other ways to simplify your language. For example, why do we “come to an agreement” (4 words, 6 syllables) when we can just “agree” (1 word, 2 syllables)? And please keep expressions like “interdepartmental synergies”, “paradigm shift”, “disambiguate” and “best of breed” where they belong. The garbage bin.

5. Have the guts to cut

If a sentence, no matter how excellent, does not illuminate your subject in some new and useful way, scratch it out.

Lesson: This point is related to Points 2 and 3 above. But it also brings to mind another important lesson: less is more. I have seen many presentations break down because the speaker tried to cover too much material. There is a limit to what audiences can retain. Cover fewer things and cover them well so that the audience remembers them. Trying to cover everything usually results in the audience remembering nothing. Not a great strategy.

6. Sound like yourself

The writing style which is most natural for you is bound to echo the speech you heard when a child. … I myself grew up in Indianapolis, where common speech sounds like a band saw cutting galvanized tin, and employs a vocabulary as unornamental as a monkey wrench. …

All these varieties of speech are beautiful, just as the varieties of butterflies are beautiful. No matter what your first language, you should treasure it all your life. If it happens to not be standard English, and if it shows itself when you write standard English, the result is usually delightful, like a very pretty girl with one eye that is green and one that is blue.

I myself find that I trust my own writing most, and others seem to trust it most, too, when I sound most like a person from Indianapolis, which is what I am. What alternatives do I have?

Lesson: Don’t try to copy others. Be yourself. Be authentic.

7. Say what you mean

My teachers wished me to write accurately, always selecting the most effective words, and relating the words to one another unambiguously, rigidly, like parts of a machine. The teachers did not want to turn me into an Englishman after all. They hoped that I would become understandable—and therefore understood. And there went my dream of doing with words what Pablo Picasso did with paint or what any number of jazz idols did with music. If I broke all the rules of punctuation, had words mean whatever I wanted them to mean, and strung them together higgledy-piggledy, I would simply not be understood. So you, too, had better avoid Picasso-style or jazz-style writing, if you have something worth saying and wish to be understood.

Lesson: Say what you mean. Of course, you can add your own style and flair, but at the end of the day, the audience has to understand you. So be clear.

8. Pity the readers

They have to identify thousands of little marks on paper, and make sense of them immediately. They have to read, an art so difficult that most people don’t really master it even after having studied it all through grade school and high school—twelve long years.

So this discussion must finally acknowledge that our stylistic options as writers are neither numerous nor glamorous, since our readers are bound to be such imperfect artists. Our audience requires us to be sympathetic and patient teachers, ever willing to simplify and clarify—whereas we would rather soar high above the crowd, singing like nightingales.

Lesson: We all suffer from the curse of knowledge. When we know something, it is difficult for us to remember what it was like when we didn’t know it. We need to step back and realize that while everything in our presentation might be obvious to us, it might not be obvious to others. And so, we often do a poor job of communicating. We need to be patient with our audiences, and design and deliver our presentations with them in mind.

In his essay, which you can read in its entirety here, Kurt Vonnegut offers a final tip, but it is related to the technical aspects of writing. For those interested, Vonnegut recommends that writers keep a copy of The Elements of Style, by William Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White close at hand. (I have had a copy on the bookshelf next to my desk for years.)

7 Replies to “8 Tips from Kurt Vonnegut to Make You a Better Speaker”

Great post John.

Very Nice!

You cover a wide range of material with class and skill.

If you ever bring out a book, I will be the first in line to pre-order or buy it.

Good Luck! Thank you for the good work.

Thanks, Dave. Happy Easter.

You too John

Thanks very much, Rashid. I appreciate it. In fact, I have been working (wrestling) with a book for some time. I am at 100 pages or so. My goal is to have it finished this year, so stay tuned.

Regarding the video that you shared, I have removed it from your comment, not because I don’t like it. I think it is great! It’s just that that video is the subject of my very next post as a natural follow-on from this one. So I didn’t want to ruin the surprise. Sorry for having to edit it out. Cheers!

Great tips from Kurt, and thanks for the great analysis John!

Thanks, Mel. I couldn’t have done it without him.